I've been an admirer of Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone since I first encountered their work in Dublin’s National Gallery as a teenager. They are huge figures in Irish art, responsible for introducing abstraction and Cubism to Ireland, even if there was initial resistance from some, and scorn from others - more on that later.

I’ve seen many of my favourite works in person, but very few side by side, and not on the scale of the new National Gallery of Ireland exhibition, Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone: The Art of Friendship.

Jellett was born in Dublin in 1897 and showed an interest in art from a young age. She was taught by other women - May Manning, Lilly and Lolly Yeats (sisters of poet WB Yeats and painter Jack B Yeats) - and studied at the Metropolitan School of Art under William Orpen. Hone was also born in Dublin, in 1894, and was a descendent of the portraitist Nathaniel Hone and landscape painter Nathaniel Hone the Younger.

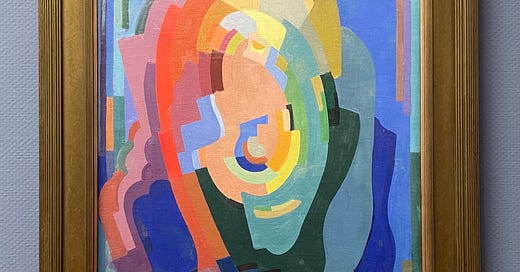

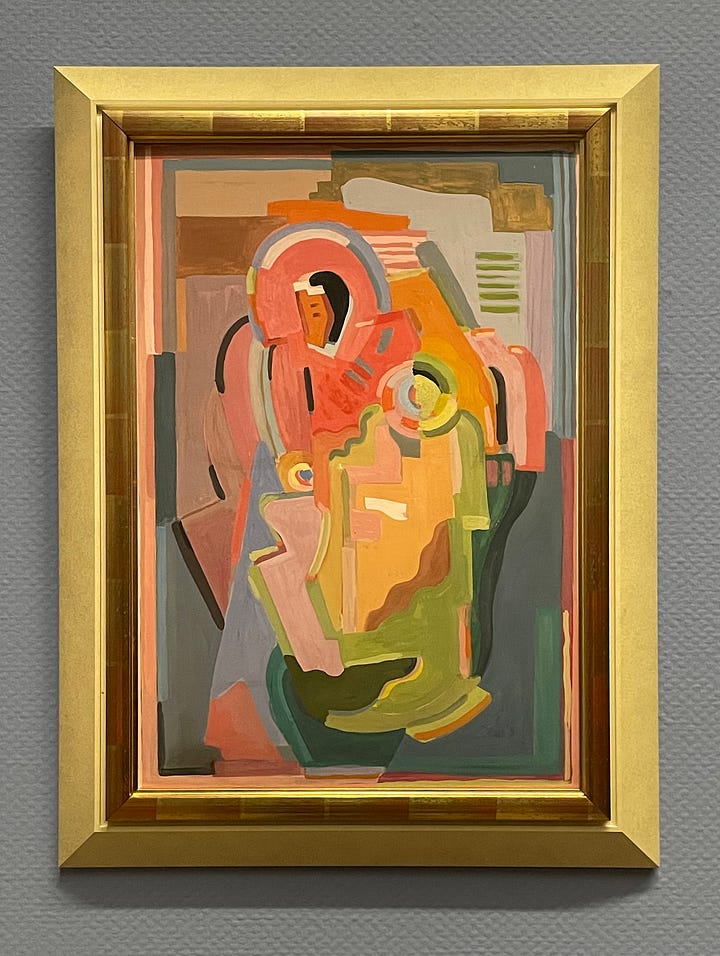

Both grew up in wealthy, Protestant families, and met in London, when they were students of Walter Sickert. In 1921, they left for Paris to study with two Cubist painters: André Lhote and, later, the more influential Albert Gleizes, who introduced them to the ideas of Translation (examining how an object exists in space) and Rotation (the relationship between objects in space). These concepts would play a huge role in the construction and layout of their future work, and both found a formal expression in Cubism. On her return in 1923, Jellett had one of her (now) most famous paintings, Decoration (1923) included in an exhibition by The Society of Dublin Painters. Like several of her pieces, it references the composition of religious paintings, specifically the Madonna and Child. Writer George ‘AE’ Russell wrote scathingly that Jellett was “a late victim to Cubism in some subsection of this artistic malaria” and described her work as “sub human art”.

What’s striking about seeing so much of their work in one room is the degree of overlap. Both were committed to “pure abstraction”: Jellett’s work often contained a central point from which all colour and shape emanate from. Hone took more risks with colour, particularly in her later stained glass work. As a child Hone suffered paralysis as a result of Polio, which affected her hands and left her with a limp. She was also deeply religious, and spent two years in a Cornwall convent, intending to become a nun. But one day, she heard a voice say: “If you stay here you will lose me”, and opted to leave (Jellett collected her). By the 1930s, Hone moved away from painting, towards stained glass and her first commissions were for church windows in Ireland and the UK. She converted to Catholicism in 1939.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Moments of Recognition to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.